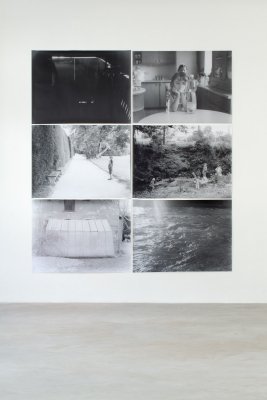

Michal Kalhous: My Father Is a Star

opening on Tuesday February 5, 6pm

6. 2. – 23. 3. 2013

From dust you shall return

(Michal Kalhous: My Father Is a Star)

It is as if I found the photos up in the attic at home in a scratched up and soiled box, together with a non-homogenous set of objects, foreign and inconceivable to the mind, but surprisingly familiar to the senses.

The most noticeable feature of Michal Kalhous’ photographs is his loyalty to material – both in the sense of an artist’s loyalty to the traditional method, as well as in the sense of a reliable traditional medium, which guarantees the continuity of substance in time and space. We do not see mere visuals; we see castings or imprints, which are carrying grains of dust from their originals. It is like when Christ’s face, in all its human corporeality, was transferred onto the absorbent material of the Shroud of Turin in order for its tangible dimensions (sweat, tears and blood) to become the keeper of the spiritual significance, which exceeds it.

The materiality of the spiritual message is not the only apparent paradox of the work exhibited. Another paradox is the relationship between reproducibility and aura. Walter Benjamin once put the unlimited reproducibility of modern work of art, especially of photographs and film, against the old fashion authority of the original. An original has the aura of the authentic here and now, which is a tangible testimony; when we look at a famous painting we believe that the tangible layers of colour and the identifiable strokes of a brush were done by that famous artist, perhaps there is even a charismatic imprint of his thumb somewhere in there, and that is almost as if we were able to touch him directly (careful, do not touch!). Benjamin was under the impression that the infinite reproducibility of a photograph breaks this bond and the aura is lost, something like when a light gets weaker when it is disconnected from its source. Today we can see that this was a hasty conclusion. A classic photograph – precisely because it is a reproduction, still refers to the original. It is not a simulacrum (an image without the original, therefore a non-image). Between the photograph and the world portrayed, there is still the relationship of a material bond between the artefact exhibited and the original here-and-now; somewhere in there, the thumb of the artist, who was stopped paying attention to his work (more precisely: who was paying attention to something else), can still be imprinted there.

Kalhous’ pictures work with aura-ism; they accentuate it. They resist the pressure of digitalization quietly but resolutely, and not only on the level of photographic technology but primarily on the level of the actual principle of reality. They refuse the digital transformation of the world and experience to a pile of indifferent number ones and zeros, atoms without compact coherence and without contact with the origin. Digital reality is immaterial but that does not make it more spiritual – on the contrary; it lacks light and its current, which spreads among different worlds and interconnects them.

Light is exactly the substance that Michal Kalhous uses to create a translucent dam to prevent the break-up of the world into disordered data. The lens – a collector of rays, concentrates what has dispersed in the daily perception. The light in Michal’s pictures is not only a surrounding, which enables to see and which puts itself outside of the centre of attention; light enters the pictures as their key actor, as stardust miraculously connecting the opposites – it is a substance, which carries a spirit, it is a material transformation, which turns a reproduction into an extension of the original; it makes the absent be present throughout time and space. The light here takes us to places and to people, which are more than mere simulacra.

However, it is no longer possible to drive off the threat of simulacrum. It is floating everywhere among us. The defence against the loss of contact with the origin (the original) paradoxically becomes the poetics of a loss, which the pictures exhibited are cultivating. It is possible to lose only something that is real. As long as we feel a loss, it connects us with exactly that thing, which is maintained, through the feeling of a loss, as precious and valuable. This way the pain from vanishing occasionally transforms to a joy from the eternal.

Martin Škabraha